It all started in 1784. The Spanish government closed the lower Mississippi River to the Americans, preventing them from trading their goods in New Orleans. Angry Kentuckians blamed the US government for not doing enough to help the situation. This caused several citizens to consider breaking away from the US. At the same time, France secretly wanted to start the process of obtaining its old colony back again by whatever means. France was also keenly aware that Kentuckians desperately needed access to markets down-river and the Gulf of Mexico for its products. But Spain saw an opportunity to stem the flood of Americans into their territory. Their solution was to convince Kentucky to become part of Spain. If they could pull it off, a Spanish-supported Kentucky would be a barrier to American expansion across the Mississippi River. The race for Kentucky was on.

-- Spanish Attempt --

|

| James Wilkinson |

|

| Gov Miro |

Wilkinson eagerly betrayed other Americans who had similar ambitions in the West in the name of protecting Spanish security. He also supplied the names of VIPs in Kentucky and Tennessee who could be corrupted by Spanish gold. Wilkinson himself enjoyed a Spanish pension of $2000 yearly beginning in January 1789, with the payments disguised as profits on tobacco sales in New Orleans. Yet, Miro saw through his scheme. When Wilkinson loaded a flat boat with tobacco, hams, butter and flour and started fearlessly on a 1400‑mile floating test voyage to New Orleans, his materials were seized in the city. Miro stated, “I am aware that it may be possible that his intention is to enrich himself at our expenses with promises and hopes which he knows to be vain.” It seems Miro knew Wilkinson had no plans to align with Spain, but instead, to break away as an independent nation. In a sly turn, Miro used the promises of future alliances to prevent a Kentuckian invasion. (Many people think that Wilkinson’s plan was to openly advocate an alliance with Spain in order to force the US to admit them into the Union. It must have worked since Kentucky achieved statehood in half the time it took for Vermont.)

-- French Attempt --

|

| Edmond Charles Genet |

At the same time, Genet speculated that western settlers, particularly those in Kentucky and Tennessee could be persuaded with “innumerable advantages” from the French government if they would only separate from the US, help invade Louisiana, and form an alliance under the protection of France. Apparently, it worked well enough in the West and even the South to get men to consider invading Louisiana. Armed bands had been gathered on the southern frontier of Georgia, and even a large body of Creek warriors was in readiness to join the invaders. It was feared at the same time, that an attack would be made from the Ohio settlements, and that the spring flood of the Mississippi would bring down the enemy, borne swiftly onward by the rising waters of that river.

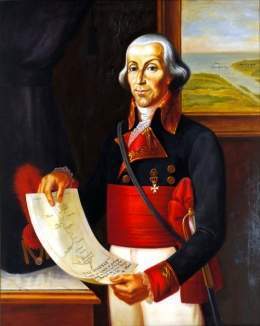

When rumors of the militia buildup reached New Orleans, Carondelet braced for impact. He formed a militia of 6000 men for the sole purpose of thwarting any attack. Simultaneously, he loosened some of the trade restrictions he had imposed on the Americans regarding passage on the Mississippi. He and Mire felt their job was to “win over that restless and energetic population to the dominion of Spain.” The Georgia governor stepped in to quell the situation. Even Washington stepped in to prevent invaders from Ohio from considering an attack. Genet’s subordinate in Kentucky, Auguste de la Chaise, abandoned all hopes and wrote a discouraged letter stating, “Unforeseen events…, have stopped the march of 2000 brave Kentuckians, who, strong in their courage, …, and convinced of the brotherly dispositions of the Louisianians, waited only for their orders to go and take away, …from those despotic usurpers, the Spaniards.” It seemed for now, there would be no invasion from Kentucky and Miro left Louisiana for Spain.

-- Spanish Attempt, Again! --

|

| Francisco Luis Hector, barón de Carondelet |

Power was an Englishman, but a Spanish subject. Carondelet thought he was a “fit subject to be employed on the hazardous mission of sowing the seeds of sedition in the West”. Power met with some of the men that would carry out the plot. He distributed a letter to them telling them that once they formally declare independence from the U.S., Spain would take possession of Fort Massac and form a new government, furnished by Spain. To entice these Kentuckians to go through with this dangerous mission, Spain gave Power $10,000 to bring up the river, “concealed in barrels of sugar and bags of coffee”, as tempting offers to smooth any difficulties along the way.

Wilkinson, still one of the most influential Kentuckian leaders, listened intently as Power flattered him, saying things such as “Can a man of your superior genius prefer to be a subordinate, a contracted position as the commander of the small and insignificant army of the United States, [versus] the glory of being the founder of an empire… the liberator of so many millions of his countrymen… the Washington of the West?”. In Power’s viewpoint, who wouldn’t want to be the George Washington of the West?

Power went on to question his zeal, asking him “Have you not the confidence of your fellow citizens, and principally of the Kentucky volunteers? Would not the people, at the slightest movement on your part, hail you as the chief of the new republic?” Wilkinson’s ego was lifted high and Power eagerly awaited to see what would happen. In a last ditch effort to plead his case, Power exclaimed to Wilkinson , “The eyes of the world are fixed upon you; be bold and prompt; do not hesitate to grasp the golden opportunity of acquiring wealth, honors, and immortal fame.”

Gayoso and Power waited. Time passed. Any insurrection that was instilled in these countrymen eventually faded away. To make matters worse for Power, Wilkinson had just been appointed Major-general of the United States and had less interest in declaring independence or worse, starting a war. Any interest in a “Spanish Kentucky” disappeared when Jay’s Treaty of 1794 was signed. Spain believed if they didn’t open up the Mississippi River to Americans, both the US and Britian would declare war. Gayoso pleaded to reverse the decision but Carondelet had made up his mind.

- http://penelope.uchicago.edu/Thayer/E/Gazetteer/Places/America/United_States/Louisiana/_Texts/GAYHLA/4/6*.html

- http://penelope.uchicago.edu/Thayer/E/Gazetteer/Places/America/United_States/Louisiana/_Texts/LHQ/1/2/Wilkinson/1*.html